The Four-State Solution

-

Otherwise known as ISIS, ISIL, Islamic State, etc. This blog will henceforth use the term "Daesh," for two reasons: 1) It's the term most used by the folks actually fighting the group on the ground, and 2) the group dislikes it, as it apparently has a pejorative double meaning in Arabic. I'm not going to pretend the recent Paris attacks didn't affect this decision.

-

Great, just what the region needs, a white guy trying to change the borders, right? That's why this post will not get into the specifics of where the new borders should be, or even whether any of the four states would subsequently subdivide further. These are questions for the parties themselves: they live there. The purpose here is to explore why partition would work.

The situation in Syria seems hopeless. A quarter of a million people have died, and millions are displaced. Daesh have internationalized the conflict by attacking Paris, Beirut, and a Russian passenger plane. In an almost absurdly retro announcement, Russia has allied with France and both countries have ramped up their involvement in the war, even as they fundamentally disagree on how it should end. And while the recent Vienna talks brought the welcome sight of Iran sitting at the table for the first time, the resulting joint statement reveals that the parties can, in essence, agree on only one thing: that Syria's "territorial integrity" should be respected — diplomatic-speak for "the borders shouldn't be changed."

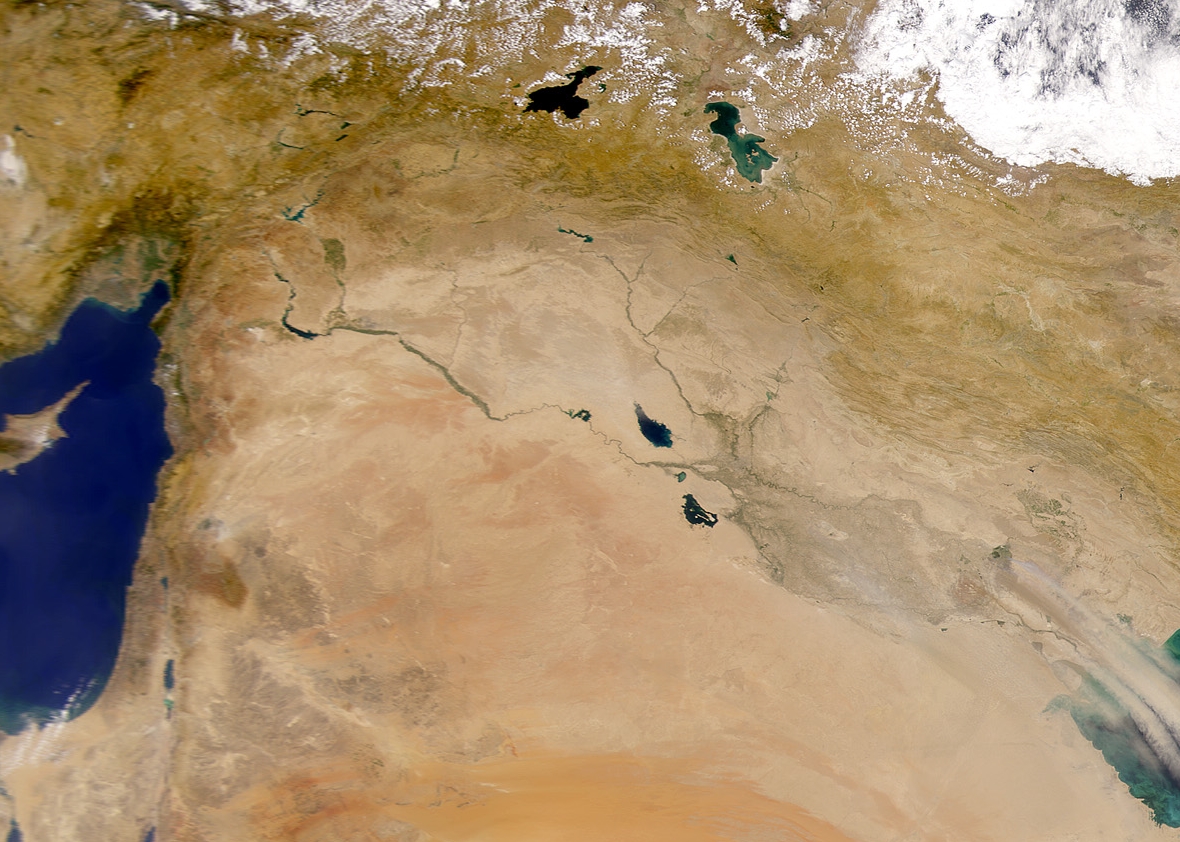

But the combatants are ignoring this demand: for some time now they have all been practicing deliberate population displacement as a weapon of war. So effective is this that, by some accounts, more than half of all Syrians have had to flee their homes, the majority internally.But in the very evil of this tactic lies, paradoxically, what could be the only viable solution to the conflict. Syria and Iraq now look less like two states and more like four: a Sunni Arab state in the center of both countries ringed by a Shiite Arab state to the east, a Kurdish state to the north, and an Alawite-led state (which would encompass other minority groups) to the west. If we recognize this, we could expedite the end of the conflict by changing the incentives of its combatants. If we fail to recognize it, the war will likely continue.

Partition brings about ugly memories: India-Pakistan, Israel-Palestine, etc. It's true, velvet divorces are rare. But the self-destruction of troubled post-Ottoman political entities isn't exactly new, and it doesn't have to end badly. Let's consider, for a moment, the Balkans.

Why do people ethnically cleanse each other?

In 1991, Yugoslavia imploded. Nationalists swept to power in most of its republics, which then began to secede one by one, first from Belgrade, then from each other. As he beheld the unfolding multi-layered ethnic war, then-U.S. Secretary of State James Baker famously declared, "We got no dog in this fight."

James Baker

This comment has been pilloried as amoral realism incarnate — not to mention grammatical apostasy — ever since, but we should not forget that Baker had good reasons for saying it. In 1991, the United States did not, in fact, have a vested interest in any specific outcome in Yugoslavia, and all sides were, in fact, committing atrocities. Today, the Serbs come in for the most opprobrium, but this is largely because they, in control of most of the former Yugoslav army, had the best weapons and the grandest ambitions. The Croats, by contrast, generally get a moral free pass for committing the largest act of ethnic cleansing in Europe since the end of the Second World War — their lightning cleansing of up to 300,000 Serbs from their ancestral homes in the Krajina in the summer of 1995. And the Kosovar Albanians — on whose behalf NATO intervened in 1999 — evicted or intimidated nearly all the ethnic Serbs out of Kosovo almost as soon as they could. Meanwhile, members of the Kosovo Liberation Army were accused (not without reason!) of trafficking organs of political prisoners.

Why did all these parties deliberately displace each other's civilians? Because in an ethnic turf battle, demography is a weapon. If Serbia claimed all lands where Serbs lived for "Greater Serbia," then Croats and Kosovars would remove those Serbs, and with them, the justification for that claim. In the breakup of Yugoslavia, ethnic cleansing was not evil for its own sake. It was a deliberate tactic to encourage national formation.

And here's the seldom discussed part: it worked. When the United States finally intervened in 1995, it was largely to protect already-established identity-based territorial units from each other. While the brief US campaign was directed against the Bosnian Serbs, America's ultimate strategy was not to pick a dog in the fight so much as give each dog its own backyard. For this reason, it was successful. Decisive victories and timely intervention and effectively "solved" the Balkans and left no room for revisionism, bringing in unprecedented peace and good neighborliness between its major groups. No one seriously considered respecting Yugoslavia's territorial integrity in 1995. Instead, they came up with a solution that worked.

Let's call it the European solution.

The Nationalizing Moment in Europe

-

In fact, the question of Kosovo bedeviled Serb nationalists for most of the 20th century. Kosovo is integral to Serb identity but by the time Serbia regained the territory in the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars, 90% of its inhabitants were Kosovar Albanians. Serb nationalists immediately began wrestling with ways to resolve this "problem," and Slobodan Milosevic's crackdown in the late 1990s was merely the latest and last attempt.

For more, see p. 23 of Klejda Mulaj's “A Recurrent Tragedy: Ethnic Cleansing as a Tool of State Building in the Yugoslav Multinational Setting.” Published in: Nationalities Papers, Vol. 34, No. 1, March 2006.

-

For more on this, please see Hobsbawm's "Nations and Nationalism Since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality," Second edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1990, page 60.

-

We need to take a brief break here to talk about how comically unworkable the Belgian government is. The country is split between Dutch-speaking Flemish and French-speaking Walloon populations, which makes forming a national government extremely difficult. Its governance crisis of 2007-08 was resolved by the selection of Herman Van Rompuy as Prime Minister, a man so unassuming he offended no one. It was said that he "only opens his mouth to breathe," a talent that so impressed Europeans that Van Rompuy was immediately plucked from his post to become the first President of the EU.

Deprived of its compromise candidate, Belgium quickly fell into another political crisis, and for nearly two years was unable to form any government at all. On the day they broke post-Saddam Iraq's record for consecutive days with no government, Belgians threw a massive nationwide party.

-

It is no coincidence that the biggest threat to the Schengen area of free movement in Europe has come not from tensions between its members but from an influx of refugees from abroad. This again shows the powerful relationship between demography and nationalism. Schengen populations can move freely but their citizenship is largely fixed. Refugees, many of whom will not be able to return home, are often given permanent residence or even citizenship, altering the long-term demographic stability of the countries that take them in.

For the nationalist-minded, a Spaniard moving to Berlin for work isn't a demographic threat: a Syrian refugee fleeing to Berlin is.

Now, is this an offensive position to hold in 2015? Of course. But that may not matter at the moment. The Westphalian order tamed the Pegidas of the world. Demographic upheaval unleashes them again. It is what it is.

The thing is, in the age of nationalism, this is generally how states have been made. We are appalled by the recentness, not the originality, of the collapse of Yugoslavia and Iraq-Syria. Earlier, this was standard nationalist procedure.

The 20th century in Europe is widely depicted as a titanic battle between liberal capitalism and totalitarian communism and fascism. But in many ways, it was truly about nationalism, about breaking down polyglot empires (Austro-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire in 1918, the British and French Empires after 1945, the Soviet empire in 1991) into nationalized states. If the borders and people didn't line up, one or the other would be moved, peacefully if possible, violently if necessary. Millions were involuntarily swapped between Ukraine and Poland, and between Greece and Turkey. A Serb agreement in principle with Turkey to deport all the "Turks" (their term for Kosovar Albanians) of Kosovo to Turkey en masse was foiled only by the death of Turkish leader Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and the outbreak of the Second World War. During the war, Eastern Europe was decimated to make room for Aryan expansion. After, millions of ethnic Germans were forcibly removed across Eastern and Central Europe. Hundreds of thousands, if not more, died migrating to a ruined and occupied Germany many of them had never lived in or even visited.

Where the state was not right-sized in the 20th century, it was homogenized by diktat in the 19th. Upon Italy's unification, Massimo d'Azeglio purportedly declared, "We have created Italy. Now we must create Italians." Indeed, from Perugia to Sicily to Lombardy, Italy was a patchwork of linguistic and cultural traditions. In some respects, it remains so. But in 1860, as Eric Hobsbawm wrote, "[t]he only basis for Italian unification was the Italian language"... which only 2.5% of the population used on an everyday basis. Similarly, in France, a country notable for its strenuous efforts to standardize and purify its national language, half of Frenchmen didn't even speak French at all at the time of the 1789 revolution, and only 12-13% spoke it "correctly." The use of public education and bureaucratic standardization allowed states to create a seemingly eternal, unified national heritage where none had previously existed: in Italy, in France, in Germany.

As a result of these two processes, by the end of the 20th century, nearly every European group that could reasonably claim a state had one — Scottish, Catalan, Basque, and Bosnian Serb aspirations notwithstanding — and nearly every state had been "right-sized" except for Belgium and, it would seem, Ukraine. As states secured their sovereignty, they could begin to give it away. Postwar Europe, in fits and starts, was able to willingly confederate into a European project that needed no army to enforce itself on the continent, but was instead built on economic policy and free movement. As before, so now. Serbia and Croatia viciously fought each other over sovereignty in the 1990s. Two decades on, Croatia has ceded much of the sovereignty it gained to Brussels by joining the European Union. Serbia hopes to do the same. What’s more, with their territory assured and the threat of the “other” removed, both countries democratized remarkably quickly, and their respect for minority rights improved rapidly. Serbia removed Milosevic. Croatia voted out Tudjman's nationalist party as soon as he died. Croatia invited back its displaced Serbs. (Most declined to return, but at least they were invited.) Serbia reached an understanding on, if not a recognition of, Kosovo. In other words, the acts of illiberal nationalist demagogues created the dynamics where liberal democracy became possible.The Nationalizing Moment in the Middle East

Which brings us back to Iraq and Syria. Their experience today looks increasingly like that of the Balkans in the 1990s. (For starters, the United States once again "got no dog in this fight.") But herein lies hope: if partition could pacify the former Yugoslavia, why not Syria and Iraq?

Some of us have felt that Iraq was headed for a breakup for some time, but it would have been difficult to support this outcome in more polyglot Syria at the outset of this war. Quite simply, the humanitarian cost of ethnic and sectarian cleansing would have been far too great, and the risk of regional instability too dangerous. But now, both of those things have happened: half of Syria's population is displaced, and most of the region and several great powers are involved in one way or another. Lebanon, Turkey, and Jordan have taken more than three million refugees alone. The threat of internationalization increases daily. The costs of the four-state solution are sunk. The benefits have still to be grasped.

And let's be clear: all the major combatants are displacing people, just on different scales. Daesh, alone among the parties, gleefully broadcasts its atrocities on YouTube, and the Syrian government's barrel bombs garner most of the headlines and outrage. But with every town they take back from Daesh, Kurdish fighters are changing the facts on the ground to ensure that their region is indisputably Kurdish. Shiite militias in Iraq are doing the same. Huge swaths of the territory of both countries have been forcibly homogenized out of a multi-dimensional ethnic security dilemma.

It would be difficult to imagine any settlement where all of those who have left are able to return home. But as the Balkans have shown, a stable, peaceful, and even democratic and pluralistic outcome can take place even if they do not.

Why the Four-State Solution Would Work

-

Note that there are multiple layers of identity here, ethnic and religious. Most Sunnis in Syria are Arab but many are not. Kurds are generally Sunni but are politically apart. Some Sunnis continue to fight for the government, and some minorities oppose it. The point is this: these identity-based division are not universal, but they are widespread and difficult to dislodge. And they must be accounted for in a political settlement.

To understand how to end the war, one must understand why the combatants are fighting it. Currently, the domestic parties, even and especially the most vicious among them, are mostly acting out of fear. (The video above, featuring a pro-regime militia commander explaining to FRONTLINE's Martin Smith why he fights for Assad, is revealing.) They either fear oppressive rule under minority dictatorship, or they fear political oblivion at the hands of a vengeful majoritarian democracy. These fears, in both Iraq and Syria, are well-founded. The four-state solution resolves them all.

Before 2003, both Iraq and Syria were ruled by ruthless Baathist regimes that were disproportionately controlled by a minority sect (Sunnis in Iraq, Alawites — who practice an offshoot of Shiism — in Syria). The U.S. invasion and imposition of elections effectively handed Iraq to its Shiite majority. The Sunnis, many of whom had been ejected from their government and army posts by de-Baathification, revolted, the insurgency began, and civil war followed. Today's Baghdad government is overwhelmingly majoritarian and Shiite-controlled. The Sunnis of Iraq will never win an election again, and they know it.

Minorities in Syria, including the Alawites (estimated to be about 12-13% of the population), Christians (perhaps 10%), Druze (3%) and others, now fear that the same will happen to them if the Assad government falls. For this reason, they will likely never accept the kind of political transition Western powers are demanding. (Nor will their backers.) Their cruelty towards civilians isn't surprising either: the decisive majority of Syria's population is Sunni and thus represents a demographic threat to the current power structure merely by existing.

The Kurds, meanwhile, are a regionally concentrated minority group in both Iraq and Syria (as well as Turkey and Iran, but that is another matter). Subject to poison gas attacks by Saddam Hussein and genocidal treatment by Daesh, the Kurds want independence. It's difficult to blame them.

All of these groups, in a united Iraq and Syria, have every incentive to continue their current behavior and trajectory. The four-state solution solves this dilemma: it formalizes the people-border alignment the parties have already created through population displacement, and thus removes demography as a weapon. Elections in the four-state solution will not be a means for one regional ethnic or religious group to demographically crush another. In other words, by acknowledging the consequences of deliberate displacement, the four-state solution removes the reason for such displacement, and indeed for the continuation of the war itself.

The four-state solution similarly resolves the seemingly intractable divisions between regional and great powers. The clear division of Sunni and Shiite spheres of influence ends the nasty proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia by giving them nothing to fight over. By preserving the current Syrian government in rump form in a new Alawite state, Russia keeps its regional and international influence, as well as what might be its only real ally. And Western powers see a return to stability and a security architecture more conducive to democracy than the current one ever could be. If no one truly wins, at least no one loses.

What about Daesh?

Actually, there is one loser: the self-described Islamic State. It has preyed on the sectarian security dilemma by appealing to Sunnis in both Iraq and Syria for whom the governments of Baghdad and Damascus are anathema. But alone among the parties, Daesh cannot ideologically endure in a territorial nation-state: it demands an ever-expanding caliphate across much of the Muslim world. And alone among the parties, it has no major international or regional backing.

So why has the United States had such trouble building an anti-Daesh coalition? Because for most of the key players, the group is the second-highest priority. Turkey has no love for Daesh but is most concerned about the Kurds. Assad and his allies are focused on any rebels who could gain Western backing. The Saudis and Qataris are focused on removing Assad. The Kurds hate Daesh but are only interested in taking back their own territory from the group. Many Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis are horrified by Daesh but fear Damascus and Baghdad more.

Even after Daesh's heinous attacks against Lebanese, French, and Russian civilians, removing them should be the second step, not the first. By trying to take out Daesh first, America and its allies are asking the combatants to act against their interest and to shift their focus away from what they see as their primary foe. This cat-herding will likely produce modest results at best. It's one thing to get the Kurds to retake Sinjar, but another to get anyone to try to go to Raqqa.

Daesh's sadistic violence has been instrumental in creating the facts on the ground for the four-state solution, but the four-state solution would ironically prove its undoing. By resolving everyone else's main conflict, it would pave the way for a united anti-Daesh campaign that is impossible today.

“Insisting on protecting Syria’s territorial integrity today makes no more sense than if the Dayton Accords had demanded Yugoslavia be put back together again.”

How It Ends

This time, the people on the ground are drawing their own borders.

-

German satirical news site Der Postillon mocked the conference by claiming that the only Syrian in attendance was a refugee working as a waiter at the Imperial Hotel.

The Vienna talks, while laudable for finally getting Iran and Saudi Arabia in the same room, had one notable absence: Syrians themselves. This seems fitting, because while the Vienna statement reaffirmed Syria's territorial integrity, the actual parties on the ground are breaking it apart. Their tactics are drawing us increasingly near a four-state solution whether we like it or not, and whether the parties intend it or not. Insisting on protecting Syria's territorial integrity today makes no more sense than if the Dayton Accords had demanded Yugoslavia be put back together again.

No settlement will bring back the dead, undo the destruction, or erase communal distrust. No settlement can justify the tactic of deliberate population displacement. And four states will not immediately end the fighting: the Sunni state will have to liberate most of its territory from Daesh's clutches, for starters. But the four-state solution will lay the groundwork for a permanent and sustainable security architecture that has not previously existed in post-Ottoman times. Best of all, it is a self-created, not imposed, solution. We, the self-described "international community," do not need to re-run Sykes-Picot and draw new borders for others. We must merely recognize the ones the parties are drawing right now through their violence. We don't need to Balkanize Syria and Iraq: Syria and Iraq are Balkanizing themselves.